Great Circles (061.03.01.00)

Properties (061.03.01.01)

Describe the geometric properties of a great circle (including the vertex) and a small circle.

(1) Largest possible circle on a sphere

A Great Circle is any circle drawn on a sphere (earth) whose center coincides with the center of the sphere, thus forming the sphere’s circumference and are the largest circles on a sphere.

Any other circle drawn on the Earth’s surface, not forming the sphere’s circumference, is a small circle.

(2) Shortest Distance Between Two Points

Great Circles provide the shortest path between any two points on the Earth’s surface, as it creates a straight line between those points. And the shortest path is always a straight line from A to B (061.03.01.01.03) .

(3) Only one connects two points

Although an infinite number of great circles can be drawn on the Earth, there can be only one (1) great circle connecting two points (unless the two points are 180° apart on the sphere (antipodal), like the poles). There can be an infinite number of small circles connecting two points.

(4) Divides the Earth into Two Equal Halves

Every great circle splits the Earth into two equal hemispheres, like the equator and a meridian with its anti-meridian. Except for the equator, every great circle lies exactly half in the Northern hemisphere and half in the Southern hemisphere.

(5) Point of greatest latitude.

The point on a great circle route where it reaches its maximum latitude is called the Vertex (north or south of the Equator). At the precise point of the vertex, the great circle track is momentarily due east (090°) or due west (270°), meaning it has no northerly or southerly component at that exact instant. After reaching its maximum northerly latitude, a great circle route must begin to turn back towards the equator to continue its path around the Earth’s sphere

Key properties of the vertex:

- It lies midway between the two points on a great circle route (in terms of longitude).

- The great circle changes direction at the vertex.

- The vertex is:

- North of the Equator for routes in the Northern Hemisphere

- South of the Equator for routes in the Southern Hemisphere

Describe the geometric properties of a great circle and a small circle, up to 30 degrees difference of longitude (061.03.01.01.02)

On a sphere (such as Earth), great circles and small circles differ fundamentally in geometry. Describing their properties over an interval up to 30° of longitude mainly highlights how these differences appear locally versus globally.

Great Circle

As stated earlier, a great circle is the intersection of a sphere with a plane that passes through the center of the sphere. Over a limited longitude span of ≤ 30°, a great circle arc:

- Appears almost straight when projected onto a plane.

- Deviates only slightly from a line of constant bearing (rhumb line), except near the poles.

- Has negligible change in curvature perceptible at small scales.

Small Circle

A small circle is the intersection of a sphere with a plane that does not pass through the center.

- The arc length along a small circle is shorter than the corresponding great-circle arc at the equator, but deviates noticeably at higher latitudes, scaling by cos(latitude).

- Locally, the small-circle arc may look nearly straight, but it is still not the shortest path between its endpoints.

Key insights:

For longitude differences up to about 30°, both great-circle and small-circle arcs appear locally similar, especially near the equator. However, only the great circle remains globally shortest and centrally symmetric, while the small circle accumulates geometric deviation as distance or latitude increases.

Name examples of great circles on the surface of the Earth. (061.03.01.01.04)

All meridians with there anti-meridians and the equator are great circles.

Convergence (061.03.01.02)

Explain why the track direction of a great-circle route (other than following a meridian or the equator) changes (061.03.01.02.01)

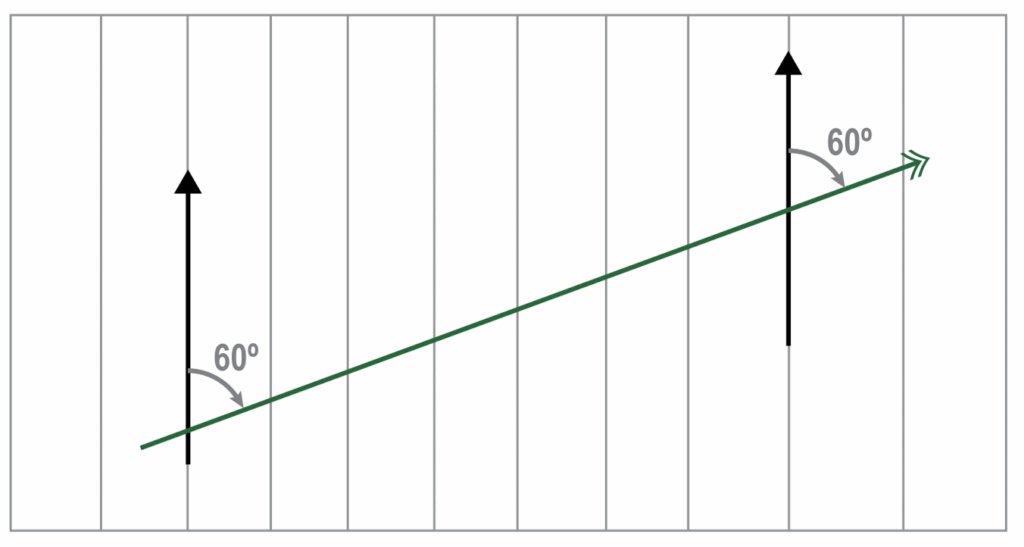

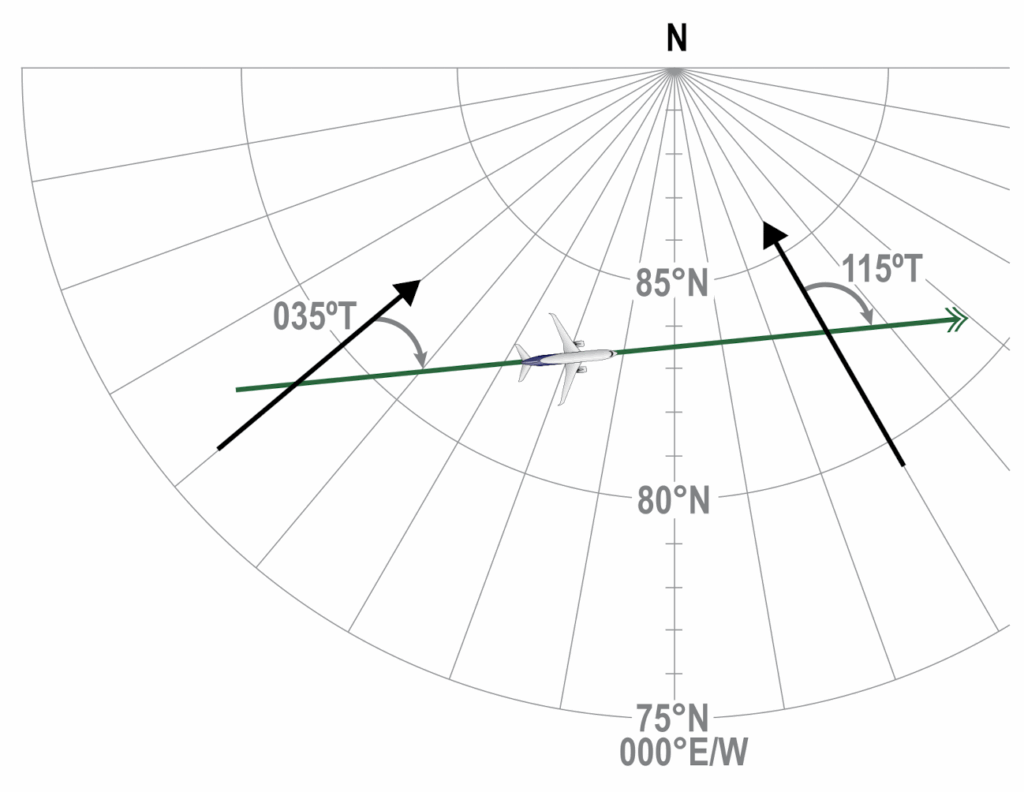

Direction is measured as an angle from a datum (reference point). In navigation, the datum is a single point, the North Pole. The meridians, the local north, converge into the pole. Because of this, straight lines drawn on the Earth have different directions along their track.

Because the change of direction on a straight line is a result of the converging meridians the effect is called convergency.

Convergency is how much the great circle track changes because of converging meridians.

State the formula used to approximate the value of Earth convergence as change of longitude × sine (mean latitude) (061.03.01.02.02).

Convergency is dependent on latitude. It is zero at the equator, where meridians are parallel and at a maximum at the poles where they converge the most.

Convergency is also dependent on how far we travel. A short track will have little change of direction, whereas a long one over the poles could go through nearly 180°.

The formula to calculate convergency:

Convergency = change of longitude (°) x sin(mean latitude (°))

In case of a Lambert conformal chart:

Convergency = change of longitude (°) x sin(parallel of origin)

Convergency = change of longitude (°) x constant of the cone

Calculate the approximate value of Earth convergence between any two positions, up to 30 degrees difference of longitude (061.03.01.02.03).

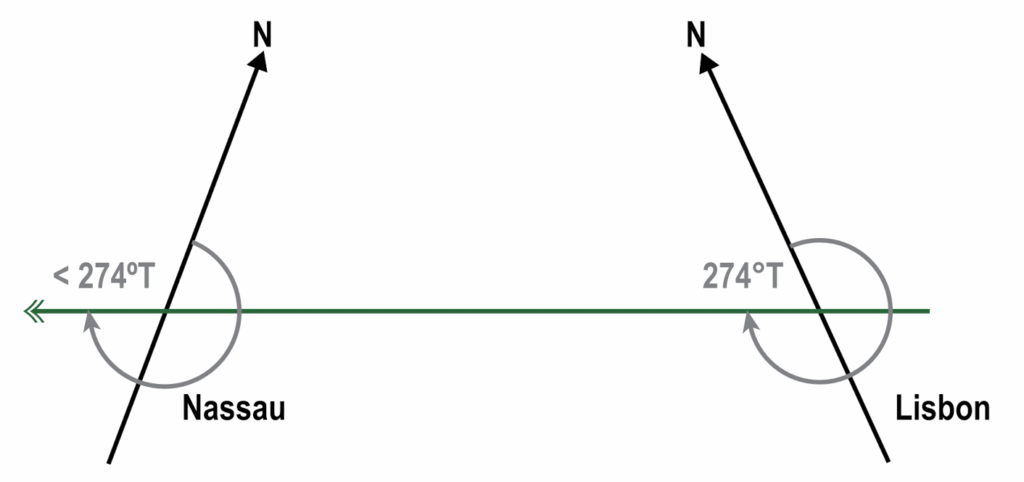

Example 1: Given that the initial great circle track from Lisbon (38°N 009°W) to Nassau (25°N 078°W) is 274°(T), find the final great circle track.

Solution:

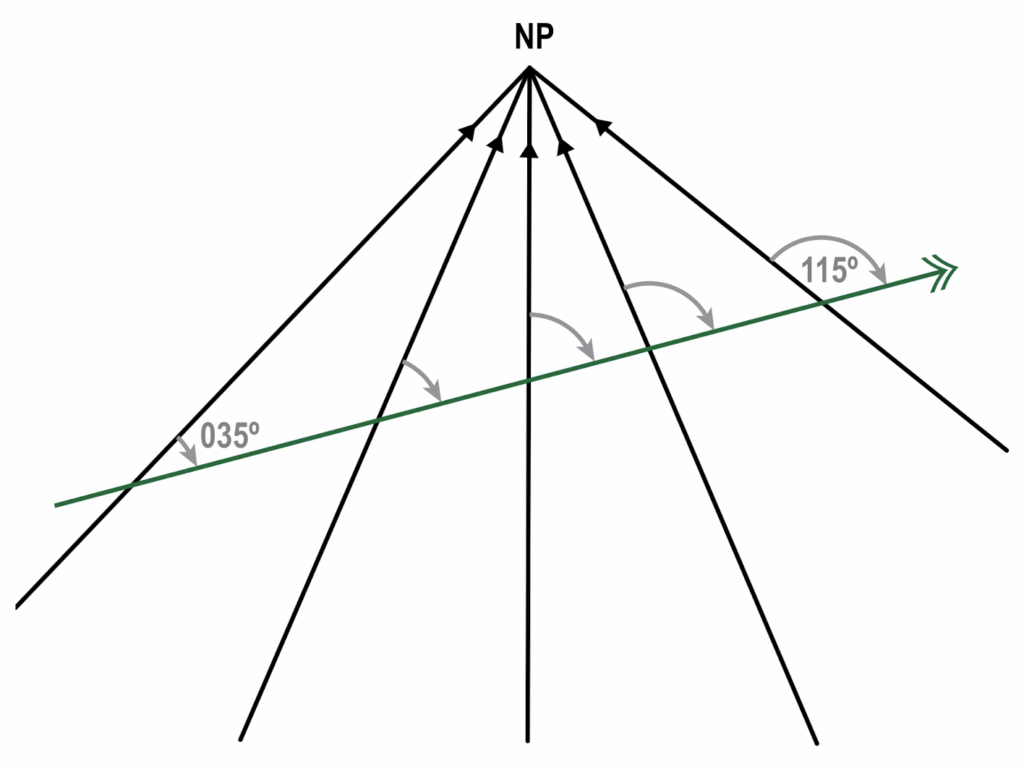

- Draw a diagram:

- with the meridians sloping-in to the north pole at the northern hemisphere, and sloping-out at the southern hemisphere.

- look at the given track, if it is generally easterly draw it left to right. If it is generally westerly draw it right to left. Make the track ends stick out beyond the meridians.

- Put in the track angle given and check if it roughly looks correct.

In this particular case the track from Lisbon (009°W) to Nassau (078°W) is generally westerly, so drawing the diagram from right to left, results in:

- Calculate the.convergency;

Change of longitude = 078° – 009° = 069°

Mean latitude = (38°N + 25°N) / 2 = 31.5°

Convergency = 69 x sin(31.5) = 36°03′ - Based on the diagram, define whether to subtract from or to add the convergency to the initial track angle given, in order to find the final great circle track.

The diagram show that the final track is less than the initial track, so the convergency needs to be subtracted from the initial track, so: 274°(T) – 36°(T) = 238°(T)

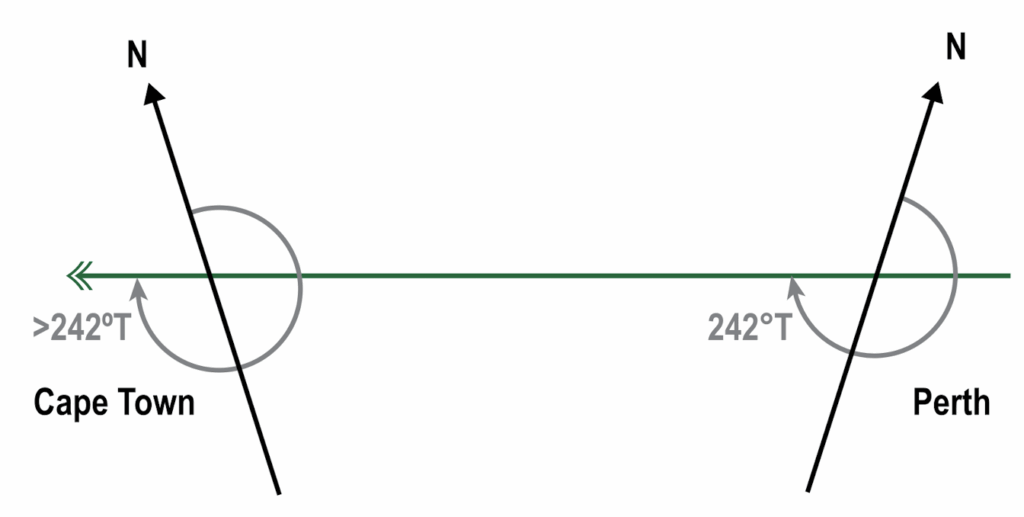

Example 2: Given that the initial great circle track direction between Perth (32°S 116°E) and Cape Town (34°S 020°E) is 242°(T), find the final great circle track.

Solution:

- Draw a diagram:

In this particular case the track from Perth (116°E) to Cape Town (020°E) is again generally to the west, so draw from right to left. And, we are on the southern hemisphere, so draw the meridians sloping-out. This results in:

- Calculate the convergency:

Change of longitude = 116°E – 020°E = 96°

Mean latitude = (32° + 34°)/2 = 33°

Convergency = 96° x cos(33°) = 52° - Based on the diagram, define whether to subtract or to add.

The diagram shows that at Cape Town the track angle must be greater than at Perth, therefore add to the initial track, so: 242° + 52° = 294°(T)

Rhumb lines (061.03.02.00)

Properties (061.03.02.01)

Describe the geometric properties of a rhumb line (061.03.02.01.01)

State that a rhumb-line route is not the shortest distance between any two positions on the Earth (excluding meridians and equator) (061.03.02.01.02).

A rhumb line (also called a loxodrome) has several distinctive geometric properties, especially in navigation and cartography:

(1) Constant Bearing

- A rhumb line crosses all meridians (lines of longitude) at the same angle.

- This means it maintains a constant compass direction throughout its length.

- For example, traveling on a constant bearing of 045° follows a rhumb line.

(2) Relation to the Sphere

- On a spherical Earth, a rhumb line is not generally the shortest path between two points (that would be a great circle), except in special cases.

- Special cases where a rhumb line is a great circle:

- Along the equator

- Along any meridian (due north or south)

(3) Shape on Different Map Projections

- On a Mercator projection, a rhumb line appears as a straight line.

- On most other projections, it appears as a curve.

(4) Spiral Toward the Poles

- Except for meridians, a rhumb line spirals infinitely toward the poles.

- It never actually reaches a pole but approaches it asymptotically.

(5) Angle Preservation

- The defining geometric feature is angle preservation with meridians, not distance minimization.

- This makes rhumb lines especially useful for traditional navigation using a compass.

(6) On the equator side.

- A rhumb line between any to points will always lie on the equator side of the equivalent great circle.

Summary:

A rhumb line is a curve on the surface of a sphere that intersects all meridians at a constant angle, appears straight on a Mercator map, spirals toward the poles, and generally is longer than the corresponding great-circle route.

Relationship (061.03.03.00)

Distances (061.03.03.01)

Explain that the variation in distance of the great-circle route and rhumb-line route between any two positions increases with increasing latitude or change in longitude (061.03.03.01.01)

Lines that are drawn with a constant direction (constant angle of the meridian), are by definition longer tracks than the great circle, which is the shortest track.

Over short distances and near the Earth’s surface, the curvature of the Earth is relative small, it appears nearly flat. In these cases the difference in length between a rhumb line and a great circle is negligible, and the rhumb line can be used for plotting the course of an aircraft.

However, over longer distances and/or higher altitudes, the Earth’s curvature becomes significant, and in those cases the great circle route is significantly shorter than the rhumb line between the same two points.

Conversion angle (061.03.03.02)

Calculate and apply the conversion angle (061.03.03.02.01)

Over short distances and out of the polar regions, the average great circle true track between two points is equal to the rhumb line true track between two points.

Conversion angle, is the angle between the great circle and rhumb line tracks at either end, and is half (½) the convergency.